“ANYONE FAMILIAR WITH YUMA, that’s driven to Yuma, knows where Roll and Tacna are. There’s about 25 people that live there. I think that was the first year of my life out there, farms and ranches.”

“ANYONE FAMILIAR WITH YUMA, that’s driven to Yuma, knows where Roll and Tacna are. There’s about 25 people that live there. I think that was the first year of my life out there, farms and ranches.”

In the mid 1970s, there was a young child growing up in Southwest Arizona. His father was a Marine, stationed a little further west in Yuma itself.

Perhaps there’s foreshadowing in the fact that someone who could lay claim to having grown the professional game in Arizona as much as anybody else spent their earliest moments surrounded by crops growing in the desert.

The boy is someone who will grow up to one day play in front of thousands on national televison, only to find himself vilified around the globe after a video posted by that same network. He’ll seize an opportunity to bring the world’s sport to a city abandoned by America’s national pastime. And one day, he’ll coach one of the game’s greatest-ever players in their final match before retirement.

But most stories don’t start in the national spotlight, and neither does this one.

***

BY THE EARLY 1990s, Rick Schantz had become one of the hotter prospects on the youth soccer scene in Tucson. He spent his days with his club out on the left wing, and in high school imagining himself as Franz Beckenbauer in the heart of the midfield for Wolfgang Weber’s Salpointe Catholic team.

Colleges came calling. San Diego. Clemson. Florida International. If he’d had his pick, Schantz would have headed to North Carolina – a propsect most attractive solely for the fact it was further away from the Sonoran Desert than he’d ever traveled.

He was no longer the young Yuma boy who crossed the border on weekends, learning to play the beautiful game alongside those several years his senior.

When Schantz moved to Tucson at the age of 11, he was still just a kid playing multiple sports. Yet there was only ever one love for him.

“I got in trouble all the time because I would bring a soccer ball to baseball practice, and I would juggle the soccer ball in the outfield while we were doing batting practice,” he says. “It’s funny, because it seemed like soccer, or football, was the only sport that I played by myself all the time. I loved it. It was really fun.”

As a baseball player, Schantz settled into a pitching role. His coaches told him that he had potential, but his heart just wasn’t in it to take it seriously enough to progress.

The same applied, too, to American football. He was a quarterback in high school, and remembers coming up against nearby Amphitheater’s notorious Bates brothers.

“I remember getting tackled one time by one of those guys and thought to myself ‘man, I’m playing the wrong sport,'” Schantz laughs. “I turned out to be a pretty big guy, but again, I played [American] football because it was fun. When it got really serious and I had to start dedicating a lot more time to American football, I was so focused on soccer.”

Focused on soccer he was. The young Schantz’s first club team in Tucson was memorable because his coach “used to smoke cigars during practice, and you would smell it all across the field.” A clash against the defending state champion CISCO Monarchs team would soon see his registration changing hands.

Despite a defeat to the superior opposition, he’d actually played fairly well in the match. At the final whistle, both coaches were talking and soon Schantz’s father was in on the conversation. The dad turned to his son, asking him if he wanted to join the opposition side.

“I said ‘OK, I want to do it,’ and I took my jersey off,” Schantz reminisces. “I handed it to my coach and said ‘thanks, this was awesome. I’m going to go play for the CISCO Monarchs now.'”

That Monarchs team was one of the jewels of the state, featuring current LA Galaxy head coach Greg Vanney as well as former Charleston Battery defender Derick Brownell. As a team, they traveled to Dallas Cup, and spent alternating weekends playing sides from California that contained future internationals such as Frankie Hejduk.

Visiting California regularly was not the hardest travel aspect of being on that team. Joining a side based in Phoenix while living in Tucson created quite the commute.

“My Dad would pick me up at 3 o’clock from Saints Peter & Paul Middle School, and drive me up to Phoenix for practice at Cactus Park,” Shantz says. “Then, after practice, we’d finish at about 7, we’d drive back to Tucson and I would do my homework.

“My dad was so committed to this that he sold the car and bought a van, and I did my homework and I slept in the back of the van on the way home. I did that from the age of about 12 until the age of 16, at least three or four times a week.”

Schantz was also working his way up within Arizona’s Olympic Development Program pecking order. In his third year of trying – and after his frustration almost saw him give up on the process – he finally cracked the national level, but world events stopped him from traveling overseas.

“We bombed Libya, and they canceled all the international events,” Schantz recalls. “No U.S. teams were leaving the country, so I missed a chance to go with the U.S. teams to France when I was 15. Then the next year, I was brought into the national camp and that was right when I tore my ACL the first time.”

By the time college choices came around, Schantz was in demand. One of the frontrunners, though, became the University of Portland.

“He was our biggest recruit that year,” remembers Darren Sawatzky, who was playing his freshman year in Portland as Schantz was finishing up high school. “He was just an absolute beast of an athlete.”

A visit to Tucson for Portland head coach and former Cardiff City captain Clive Charles helped to win Schantz over.

“Clive came down to Arizona to watch me play, and we went to dinner,” he says. “My family went to dinner with Clive at his hotel, and it was just so impressive speaking to him and listening to the things he was speaking about, about learning the game and the way he envisioned me playing football.”

It took a trip to Oregon to see his future teammates face the Canadian Olympic team to seal it, but sure enough, Schantz was going to be a Portland Pilot.

***

SEVERAL YEARS AGED, college senior Rick Schantz sat in Clive Charles’ office.

“I was probably the biggest pain in his butt,” Schantz says, reflecting on his time in the Pacific Northwest. “I had so much ability, or I would say potential. For some reason, I was afraid to make mistakes. I didn’t want to let anyone down. So the harder you were on me to perform, the more rigid I played, almost robotic.”

His introduction to college soccer had been far from easy. ACL problems kept him off the pitch throughout his freshman year.

Away from the stadium, Schantz was a criminal justice and psychology major, with a minor in philosophy. Eventually, as part of his capstone project, he would interview prisoners on death row. But the freshman Schantz was not yet fully enamored by the academic pursuits of higher education.

“Rick never turned down a beer, I’ll say that,” Sawatzky points out. “He’s a great guy. He’s a happy guy. He wants to have fun all the time.”

Schantz ultimately graduated with a 3.0, having “learned how to be interested in school, I learned how to be excited.” But that wasn’t the only adjustment needed, with Schantz unaware and at times completely unprepared for aspects of the college year, such as his first spring break.

“Most kids go off to frickin’ Pensacola Beach and Cancun and sh** when their parents pay for them to go,” Sawatzky recalls. “Neither Rick or I grew up in households that had any money. We were sitting talking a few days before spring break came up, and he basically told me the day before I was leaving ‘well, I’m just going to stay on campus.’

I’m like ‘Rick, you can’t. They shut the campus down.’ So he basically just defaulted and went on spring break with me, home to my house in Seattle.”

When he did get on the pitch, though, Schantz showed off his talents.

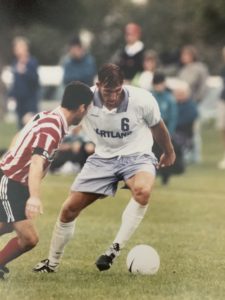

“He had a wicked left foot,” Sawatzky says. “When you looked at him, you thought he was a center-back. He was a left-flank player, left wing-back type, left winger. He looked a lot bigger. He had good feet. He has soft feet for a big, strong guy, but his athleticism was the thing that really stood out.”

Most memorable from his years in Portland was a run to the final four in his junior year, but Schantz’s appearance on the national stage almost didn’t happen.

Rehabilitating from yet another ACL injury, he was training in Portland for the big game when his knee brace got caught on the frozen ground.

“They said this was indestrucible and I broke it,” Schantz says. “I remember coming off the field after I heard this brace snap in half, and they said go see the trainer, and I was so angry, I took my knee brace and I hit it against the fence post and it broke in two pieces.

“I walked into the training room and I showed them my brace. The guy almost fell over. He was like ‘oh my good, is your leg OK?’ They thought I had shattered my knee and I’m standing there and I’m like ‘no, I broke this damn brace.'”

Despite being unable to find a replacement brace in time, Schantz still played on ESPN in front of 21,319 fans as his school fell 1-0 to the eventual national champion Wisconsin Badgers.

That next year, before taking the field for another match, was when he found himself sitting in Clive Charles’ office.

“He said ‘you’re not going to be a pro. You’re not good enough. You’re not dedicated enough. You’re not focused enough, and I just want you to enjoy your last season here at the University of Portland,'” Schantz says.

“I walked out of the office angry. I thought ‘I’m going to show this guy,’ and I had probably my best season at the University of Portland.”

Looking back now, Schantz lauds the approach from his former coach, who seemed to always know how to treat his players to get the best out of them.

He isn’t alone in remembering Charles fondly.

“I think it’s just a real shame that Clive wasn’t able to see the effect that he had on a lot of people, because I think his reach would have been even farther reaching than it is now,” Sawatzsky says. “When he passed away in ’03, he couldn’t continue to be the mentor that he was. I think that there are a lot of coaches out there that couldn’t tie Clive’s shoes.”

While Charles may not still be around to help, that doesn’t mean that his lessons weren’t received.

“I look back now on that conversation, and clearly I understand that he knew what it took to get me motivated to perform,” Schantz says. “Now as a coach, I kind of think, the way you communicate, and the way you have to find what works for players, it’s different. Not all players are the same. That’s the one thing that I really learned from him. He treated us all as individuals, and he tried to find the best way for us to perform and to be successful, and that’s truly caring about your players.”

This is the first of a three-part series on Phoenix Rising coach Rick Schantz.

Part II, focusing on Schantz’s return to Tucson, can be read here.

Part III, focusing on Schantz’s experience in the professional game in Phoenix, can be read here.